A Shining Moral Hero Abandoned in the Dark

- Share via

WASHINGTON — If he had chosen his enemies more cleverly, Wei Jingsheng would probably be a household name by now--like Vaclav Havel, Andrei D. Sakharov or Nelson Mandela. A leading voice in China’s Democracy Wall movement of 1978, Wei is his country’s most important political prisoner.

China’s leaders despise him. Western heads of government--including President Bill Clinton, who announced last week that he wants to grant China most-favored-nation trading status and is preparing for a summit meeting with Chinese President Jiang Zemin this fall--like to pretend Wei doesn’t exist. Championing Sakharov during the Cold War was ideologically useful for capitalist governments, but defending Wei would jeopardize access to the biggest potential market in history.

Ignoring Wei is becoming more difficult, however, with the publication of “The Courage to Stand Alone,” his fierce, earthy, darkly comic prison letters. Now reportedly near death after 18 years behind bars, Wei and his book were recently honored in absentia at the New York Public Library, where Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani and some of the city’s most important writers and artists--playwright Arthur Miller, novelist E. L. Doctorow and musician Peter Gabriel, among them--read from and saluted Wei’s writings. Wei’s most effective stand-in was an unrecognizable Gabriel, wearing a buzz cut that eerily recalled the shaved head Wei was given before his 1979 show trial.

Predictably enough, Beijing denounced the event, demanding that Americans who “know little or nothing” about Chinese law stop treating Wei as a hero.

But what other word is there for a man who could write the letter Wei sent to Chinese Premier Li Peng on May 4, 1989, a month before the Tiananmen crackdown? At that point, students had been occupying the square for weeks, average citizens were rising to support them and the world’s television cameras were recording the whole drama. Wei had been in jail for 10 years, mostly in solitary confinement. He had been beaten, tortured, kept in sub-freezing cells and lost all his teeth. Yet, he wrote to Li with the same towering self-assurance Mandela showed in prison, lecturing and negotiating with his jailers as (at least) their equal. Wei warns Li not to follow the lead of Deng Xiaoping, who is “senile” and bringing “ruin upon himself.”

But Wei is shrewd enough to know that Li may have to placate party hard-liners, so he urges him to “use my continued imprisonment” as a bargaining chip. If it would secure the students’ reforms, Wei writes, he would feel “extremely honored” to remain in jail a few more years.

In a written message of solidarity to the New York event, Havel noted he has nominated Wei for the Nobel Peace Prize, and it is plain from “The Courage to Stand Alone” that Wei does rank with Havel, Mandela and Sakharov as one of the moral giants of our time. Alas, few other world leaders have dared speak up for Wei. Vice President Al Gore, for example, never publicly uttered the words “human rights” during his visit to China in March. French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac, perhaps grateful for the $1.5 billion worth of airplanes China ordered from Airbus Industrie, was equally quiet during his Beijing visit earlier this month.

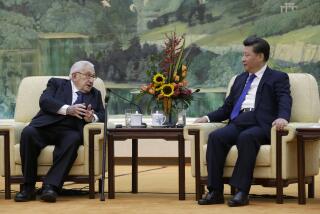

The Clinton administration abandoned its initial human-rights activism toward China in 1994 in favor of a corporate-friendly policy of “quiet diplomacy.” As Richard Bernstein and Ross H. Munro describe in their book, “The Coming Conflict With China,” this policy shift was a resounding victory for the “New China Lobby.” In return for hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees from such clients as Coca-Cola, United Technologies and American Express, former Secretaries of State Henry A. Kissinger and Alexander M. Haig, along with other former top U.S. officials, pressed hard to “delink” human rights from U.S. trade policy toward China. Thus, current U.S. policy regards human rights as “one consideration among many” in U.S.-Chinese relations.

Representing the administration at the Wei tribute was John H. Shattuck, the assistant secretary of state for human rights. Shattuck met with Wei in Beijing in February 1994, when Wei was briefly released from prison--in a transparent effort to bolster China’s campaign to host the 2000 Olympic Games. (Wei’s price for agreeing to leave jail early was the return of the many letters he wrote in jail, hence this book.)

Wei told friends he expected to be thrown back in prison soon, but when he was, Shattuck was blamed. Quiet diplomacy advocates seized on Wei’s rearrest as proof that Shattuck’s style of activist diplomacy was counterproductive, a charge human-rights activists ridicule. “Look at the numbers,” says Abigail Abrash of the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Center for Human Rights. “The original policy of linkage did produce releases of dissidents like Harry Wu, Chen Zeming and Wang Juntao, while the new ‘quiet diplomacy’ has yet to prove its effectiveness.”

When Shattuck began his remarks at the New York Public Library by saying he would read a message from Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, ears pricked up across the room. Perhaps a change was in the offing. But the message itself--two sentences praising Wei’s “courage and tenacity” but containing not a single word promising action on his behalf--was very quiet diplomacy indeed.

By contrast, Robert L. Bernstein, the chairman of Human Rights Watch, conceded that relations with China are complicated but added, “What I am asking tonight is not complicated. President Clinton must delay any summit meeting with President Jiang until Wei Jingsheng is released from prison and allowed to express himself safely.”

The best retort of the night, though, came from Doctorow, who invited fellow authors to join him in refusing to allow their books to be sold in China until Wei is released. “It is really a private matter, of no great consequence,” said Doctorow of his proposal. “But we will at least have the satisfaction of knowing we have done more to stand in solidarity with Wei Jingsheng than the U.S. government or corporations have done.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.