Microbes: A Gene Hunter’s Latest Quarry

- Share via

ROCKVILLE, Md. — It took a few years for the world to realize how powerful Craig Venter’s blitzkrieg gene-hunting method would be for understanding the human genetic code. But when he modified his technique and moved on to microbes, the reaction was immediate.

“The first dozen organizations into our Web site when we published the paper in July of ’95 were every major pharmaceutical company in the world,” Venter says with pride.

The paper described the complete genetic blueprint of Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium that causes ear infections and meningitis in children. Having the genes of Haemophilus--or any other microbe--could help drug researchers develop more effective antibiotics at a time when infectious organisms are becoming frighteningly resistant to current ones.

On the to-do list of Venter and his colleagues are a host of names virtually synonymous with human misery: Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vibrio cholerae. Not to mention Borrelia burgdorferii, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, and the ulcer-causing bug Helicobacter pylori.

“We’re doing the three biggest killers in the world,” Venter says, referring to ongoing projects to catalog the genetic material of the microbes that cause tuberculosis, malaria and cholera.

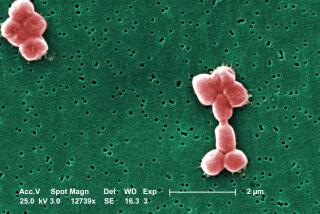

But his favorite microbe of all is Deinococcus radiodurans, a bacterium that can withstand ridiculous amounts of radiation, survive in the complete absence of water and revivify itself from spores that have been around for eons. Its genes could reveal how the bacterium does all that.

“It’s one of the most remarkable things we’ve ever seen,” Venter says. “We’re really looking forward to getting insight into that organism.”