NEWS ANALYSIS : For Aspin, This Was the Year From Hell : Defense: His regime at the Pentagon began in dispute over gays in the military. It became mired in criticism over Somalia, Bosnia and Haiti.

- Share via

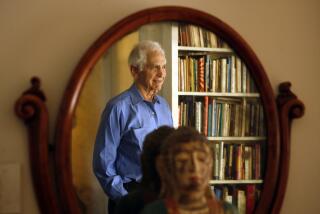

WASHINGTON — In 22 years in the House, Les Aspin slowly made himself into one of the most powerful barons of Congress on military issues and national security.

But in the 12 months since he accepted President Clinton’s offer to become secretary of defense, the position for which his whole career in Washington seemed to have prepared him, Les Aspin lived a nightmare--a year from hell that ended with his resignation under pressure on a cold and rainy winter’s evening.

Starting with the Pentagon’s rebellious battle over gays in the military and stretching through the grinding frustrations of Washington’s inability to apply its superpower status to such trouble spots as Somalia, Bosnia and Haiti, Aspin’s year at the Pentagon bore little resemblance to the exercises in grand strategy and military reform that were dear to his heart.

Intellectually impressive but chronically disorganized, Aspin was sorely miscast at the Pentagon, an institution that prizes organization over intellect.

Moreover, he tried to run the Pentagon--the nation’s largest bureaucracy--the same way he ran his office on Capitol Hill: Instead of building an all-embracing network of appointees who could see that his wishes were followed--and provide crucial warnings of impending trouble--he worked almost exclusively with a small group of aides, many of them from his old congressional staff.

They knew Aspin and they knew the issues but they did not know “the building,” as Pentagon veterans call it. Often impatient with its ingrained ways, the Aspin team tended to get crossways with the institution on matters large and small.

Even when he was reflecting consensus views, Aspin’s shambling, professorial manner made him a less-than-commanding spokesman, at least in the military’s eyes.

As a result, the secretary’s relations with the uniformed services--strained from the beginning--never jelled.

“Folks at the Pentagon never took to him, which was part of his problem,” a former high ranking Pentagon official said. “He was always a poor advocate on behalf of the Pentagon--in front of cameras, in front of Congress or in public.”

If he never quite got the military under control, Aspin had his troubles with Congress, the public and White House, too.

In naming the former chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Clinton clearly hoped to gain credibility on Capitol Hill. But in Aspin’s troubled year, some of his worst defeats were suffered in Congress.

Within days of Aspin’s arrival in office, Administration defense policy was overshadowed by a bruising fight over Clinton’s campaign promise to allow gay men and lesbians to serve openly in the Armed Forces. The services rebelled publicly.

Aspin tried to cobble together a compromise that would keep Clinton’s promise. But ultimately, the Administration had to go along with the “don’t ask, don’t tell” plan advocated by Sen. Sam Nunn (D-Ga.), who appeared to miss no opportunity to humble the new Administration.

The controversy damaged the relationship of both Clinton and Aspin with the uniformed services. Clinton was able to go on to other issues but Aspin remained mired in the distrust of the services he was appointed to lead.

Then there was the episode in Somalia when U.S. Army Rangers were caught in an ambush and U.S. commanders did not have the tanks and heavy armaments they needed for a prompt rescue. Eighteen Rangers died.

When it was learned that the commanders had requested such equipment and warned that they could not protect American lives under some circumstances--communications that Aspin had not acted upon--the secretary acknowledged that he had made the biggest mistake of his tenure at the Pentagon.

Aspin also drew widespread criticism from the defense Establishment for slowness in getting a team in place. In part, he was hamstrung by White House insistence on playing a major role in personnel decisions--a tendency that has plagued the whole Administration. And some of the choices proved controversial in Congress.

Many senior military officers also said that they believed Aspin and his inner circle were too busy worrying about strategy to focus on the needs and views of the armed forces.

All this appeared to add up to an abdication of the defense secretary’s first responsibility: to protect the armed services.

And Aspin’s troubles at the Pentagon repeatedly boiled up into trouble for Clinton and the White House--troubles that were especially unwelcome because Clinton is considered politically vulnerable on issues involving the military and because the controversies interrupted the President’s desire to keep his focus on domestic issues.

In fairness, Aspin was slowed significantly by serious heart problems that flared up last February and the subsequent installation of a pacemaker. Aides said that his resignation had nothing to do with health, but it was clear that his medical problems hampered his effort to master one of the most demanding jobs in the world.

Although both Aspin and Clinton presented the defense secretary’s departure as a resignation, there was strong evidence that he was pushed.

“I think Les Aspin was as surprised by his resignation as the rest of us,” former Secretary of State Lawrence S. Eagleburger said in a CNN television interview.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.