Trial of Former Owners Nearing Climax : Ramona Always a Fraud Target, Jury Told

- Share via

In the first criminal trial involving owners of a failed Southern California thrift, the prosecution told jurors Wednesday that the former top officials of Ramona Savings & Loan in Orange were engaged in deception and fraud “right from the get-go.”

“This was a federally insured savings and loan institution. We are not talking about some piggy bank or some toy,” Assistant U.S. Atty. Steven E. Zipperstein said during closing arguments in the 11-week-old trial in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles.

Ramona collapsed in September, 1986, and subsequently required a $65.5-million federal bailout of depositors.

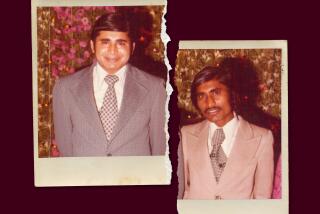

John L. Molinaro and Donald P. Mangano Sr. each face more than 30 charges, including bank fraud and conspiracy, in connection with a Palm Springs real estate deal that prosecutors allege led to the thrift’s collapse.

Mangano’s attorney, Robert S. Horwitz, began his closing arguments by questioning the veracity of some of the people who testified for the prosecution.

“We believe a number of key government witnesses did not keep that promise to you (the jury) to tell the truth,” Horwitz said.

He pointed out what he said were numerous inconsistencies in testimony, including talk about Mangano’s profit from the real estate deal. Horwitz labeled some of the testimony “so much rubbish.”

Mangano, a real estate developer, and Molinaro, a former carpet salesman, bought Ramona in April, 1984, and spent about $25 million, or a quarter of the thrift’s assets, building Cherokee Village condominiums.

The project, which the government alleges was designed to enrich the two men rather than Ramona, was a failure. Only seven of Cherokee Village’s 180 units had been sold by the summer of 1985.

Zipperstein said Wednesday that Molinaro and Mangano dreamed up a complicated scheme to sell Ramona before the thrift became insolvent and Cherokee Village went bankrupt.

The two men set up four dummy corporations. Ramona then recorded a sale of the Cherokee Village resort to three of those corporations for a $30,000 paper profit per residential unit. Mangano then had the stock in those corporations transferred to him.

The government said the sale was done to make Ramona, which recorded a $4-million profit on the deal, look healthier to a potential buyer and to forestall a takeover by regulators. Molinaro took a $2-million dividend from Ramona around the same time.

Once the two men found a buyer, they allegedly transferred the liability of Cherokee Village back to Ramona disguised as a land acquisition of 23 acres in Palm Springs. No mention was made of Cherokee Village.

But the defense said the government’s allegations were unfounded. Horwitz said the dummy corporations were set up for tax reasons and because Mangano wanted to protect his credit worthiness in the event Cherokee Village failed.

Horwitz said plenty of people knew about the transaction, including one of the thrift’s attorneys and an insurance representative. He said the $30,000 profit that was booked per unit was done without Mangano’s authorization and was an accounting error.

Partners’ Net Worth

The defense added that each man had a net worth sufficient to cover debts associated with Ramona. Molinaro had a net worth of $11.8 million at the time of Ramona’s collapse; Mangano $5 million.

If convicted, Molinaro--sole owner and operator of Ramona at the time of its collapse--faces a maximum prison sentence of 165 years and $8.3 million in fines; Mangano could receive a 155-year setence and $7.8 million in fines.

The Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp. has filed a civil lawsuit seeking more than $65 million in damages from Molinaro and Mangano, alleging that the two men began pilfering from the thrift almost as soon as they bought it. The civil case is not expected to go to court until at least December.

The current proceedings are scheduled to continue today with closing arguments by Molinaro’s attorney.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.