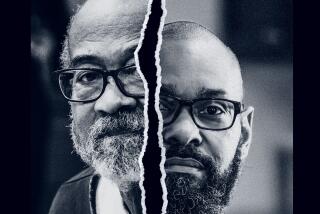

Bright, Compulsive Felon Is Baffled by Wasted Life

- Share via

Oh why oh why do I compulsively burgle?

Terrence Lee Liddell asked that question in a poem he left behind after breaking into a Tarzana home. As he usually does when he is not in prison, he had pedaled his bicycle through streets he has known since his youth, monitoring a police radio before deciding on his targets for the evening.

Liddell, 42, is one of the most active felons in the San Fernando Valley. He has struggled to understand why he settled into a most peculiar pattern of crime, but has come up with few answers.

Liddell describes himself as a “boy hiding in a man’s body,” someone who commits crimes almost on a dare, challenging authorities to catch him.

Police describe him as a menace to society, a man who prowls the streets of the West Valley nightly, breaking into several homes in a single outing, and who has tried to rape more than two dozen women over the years.

But the police don’t pretend to understand him, either, this break-in artist who could leave behind a poem.

26 Years in Prison

Liddell, who grew up in Encino and Reseda, has been incarcerated at least nine times since age 14 for burglaries, robberies and sex offenses. He has spent nearly 26 years behind bars. He is in Los Angeles County Jail now, awaiting trial on 17 felony charges.

Each time he was released from custody, Liddell returned to commit new crimes in Reseda, Tarzana and Encino, and was rearrested within months of his parole. His longest period out of jail since 1957 was a one-year stretch from Nov. 1, 1975, to Oct. 31, 1976, court records show.

Liddell’s record has frustrated police officers and prosecutors. He commits crimes with staggering regularity, but, like other career criminals who have not caused “great bodily injury” to their victims, he falls outside the bounds of a state habitual-offender law that provides for life imprisonment.

“He should be put away forever. This guy doesn’t belong on the streets with you and me,” Los Angeles Police Detective Bud Mehringer said.

A Self-Appraisal

Liddell at times complains that the criminal justice system has “thrown in the towel” on him, abandoning rehabilitative efforts in favor of retribution. He argues that only intensive psychotherapy will lead him to productive behavior. In the next breath, however, he says the behavior may be irreparable.

“I suspect I was somehow born the way I was--a bad seed, perhaps, or born with certain negative tendencies,” Liddell wrote to a reporter from jail. “And it would have taken very skilled intervention to divert nature’s initial course.”

The profile of this “burglar on the block,” as Liddell calls himself, is fraught with contradictions.

Liddell is an intelligent man. He made literary references during each of four jail house conversations with a reporter; he has published several magazine articles about prison life. He also masterminded his escape and that of six others last year from the maximum-security section of Peter J. Pitchess Honor Rancho in Castaic.

At the same time, police say that Liddell, a “creature of habit,” was foolish enough after the escape to return to his old neighborhood--into the waiting arms of the law.

He is a soft-spoken, shy man with thinning gray hair, 6 feet, 2 inches tall and 210 pounds, who terrifies women by breaking into their homes and making sexual advances. He typically flees, however, when he encounters resistance or a scream. Although his record includes several attempted-rape convictions, he has never been found guilty of what is legally termed forcible rape.

When he leaves, he often advises women victims how to secure their homes against intruders. On one occasion he returned $10 of $50 he had stolen from a woman, telling her that he didn’t want to leave her broke.

Boy Scout of the Year

He was Boy Scout of the Year for Troop 178 in Encino in 1956, the year he began burglarizing neighbors’ garages.

Liddell describes himself as a fusion of four fictional characters: Holden Caulfield, the 17-year-old struggling to find himself in “The Catcher in the Rye”; Alexander Portnoy, the sexually obsessed protagonist in “Portnoy’s Complaint”; the adventurous Tom Swift, and the neglected child, David Copperfield.

One longtime acquaintance, citing Liddell’s reputation as an electronics crackerjack, called his crime-filled life “the most pitiful case of waste of a human being. . . .

“He’s got a split personality. He’s out for 10 minutes and he’s back at it. Something just goes ‘click,’ I guess.”

Liddell is primarily a burglar who steals cash and jewelry, Detective Mehringer said. But he is also a “rape opportunist,” someone who sexually assaults women if he finds them alone in their homes, the detective said.

Asked to explain his aberrant behavior, Liddell blamed everything from falling off a swing and landing on his head at age 3 to a now-discounted 1960s theory that men with an extra Y chromosome are genetically inclined to a life of crime.

But, when pressed, Liddell concluded, “Oh God, I wish I knew.

“Maybe I’m just looking for excuses. I’ve got to face the fact that I really did screw up.”

Fear not, for I have taken nothing--except perhaps your peace of mind. . . .

After breaking into a writer’s home in Tarzana in March, 1985, Liddell composed a short letter on the man’s typewriter and left it among the pages of his latest work. He explained in the letter, almost by way of apology, that he had entered the home to get out of the rain, remembering from a previous burglary of the house that the writer had a “magnificent library.”

Liddell recalled a short story about a burglar who established a rapport with a writer and periodically broke into his home to critique his latest work.

After suggesting that perhaps he and the writer could develop a similar relationship, Liddell abandoned the idea, saying:

“More likely, another visit in the near future would be met with a securely locked door, alarms, lights, mad dogs, booby traps, atomic bombs and whatever other technological paranoia suburbanites are arming themselves with these days.”

Reassured Victim

He then reassured the writer that his visit was innocuous, concluding:

“Fear not, for I have taken nothing--except perhaps your peace of mind at having your sanctuary invaded (and I hope not too much of that). Not too much peace of mind, that is.”

Liddell also typed out a six-line poem, which began: Oh why oh why do I compulsively burgle? / With each night, a new odyssey dawns in nocturnal serenity. / And off I go towards another serendipitous adventure.

The verse is consistent with a description Liddell recently gave of his burglary compulsion. He called himself a “Jekyll and Hyde” character who has a “retarded daytime personality” but who grows brazen with the fall of darkness.

“Being hidden away in the shadows had an effect somewhat like alcohol and other drugs on one’s inhibitions,” he said.

Liddell’s sexual crimes, he said, arise from a “nearly impossible” fantasy: He breaks into a woman’s home and startles her in her sleep, but she is soon “swept away” by the thought of making love to a stranger.

Liddell titles the fantasy, “Walter Mitty Meets Mrs. Robinson.”

Liddell has an answer to those he terms “amateur psychoanalysts,” who, he says, have suggested that his sexual obsessions mean that he hates his mother.

“I’m not Tony Perkins,” he said, referring to the actor’s role as the homicidal son in the movie “Psycho.”

To the victims, I’m Charlie Manson with a hatchet coming through the door. To the authorities, I guess I look like a gargoyle with the fangs and a knife.

Liddell is candid about his criminal offenses, admitting to most of the acts he has been charged with over the years. However, he would not discuss the charges pending against him, which stem from crimes that took place before his incarceration in Castaic and during the month he remained a fugitive.

Those charges include seven counts of burglary, two counts of assault with intent to commit rape and one count of auto theft. Prosecutors also believe that, for the first time, they have strong evidence linking Liddell to a forcible rape, committed March 25, 1985. The victim, who thought the suspect had a weapon, identified Liddell in a lineup, investigators said.

A preliminary hearing is scheduled April 7 in Van Nuys Municipal Court.

Mehringer has interviewed several of Liddell’s sexual-assault victims. Some of the women “will never be the same again,” he said. “They’re hysterical; they’re very fearful.”

A recent probation report quotes some of his victims as saying they hope Liddell is imprisoned for the rest of his life.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Edward G. Feldman, who is handling current charges against Liddell, said that when the complaint was filed in November, 1984, prosecutors attempted to apply a “habitual offender” statute against Liddell. That allegation, if proven in court, would have made Liddell eligible for a life prison term, with no possibility of parole for 20 years.

However, the law requires that, besides proving that the defendant is a career criminal, prosecutors also must show that he has inflicted “great bodily injury” on a victim. The allegation was withdrawn for lack of such evidence, Feldman said.

Simulates Gun With Flashlight

Court records show that Liddell isn’t known to have struck any of his victims. In one incident he carried a broken BB gun, and he typically puts a penlight flashlight to the back of his victims’ heads, like a handgun, Mehringer said.

“To a lay person, Terrence Liddell would definitely fit the category of a ‘habitual offender,’ ” Feldman said. “But the Legislature made it clear that the life-imprisonment statute was intended only for violent offenders, and the state Supreme Court has concluded that even a rape, by itself, does not constitute ‘great bodily injury.’ ”

Feldman said he believes that Liddell knows exactly where California’s life-imprisonment threshold lies and is careful to stop short of violence. “He’s obviously a very intelligent individual who understands the system very well,” the prosecutor said.

Although that habitual offender law does not apply, Proposition 8, passed in 1982, did give prosecutors some additional ammunition against criminals such as Liddell. It enables them to seek extra years in a jail term if a defendant has been convicted of certain other felonies. If Liddell is found guilty of any of the pending charges, prosecutors could argue for a sentencing enhancement of 17 years based on earlier convictions, Feldman said.

Liddell could receive more than 50 years in prison for the pending charges. But because prosecutors wanted to spare his victims the ordeal of testifying, he was offered a plea bargain under which he would have been sentenced to 25 years, eight months, in state prison. That would have made him eligible for parole in about half the time. He rejected it.

Liddell argues that he could benefit from psychiatric treatment in a mental hospital. But, he laments, “society seems more interested in revenge than in rehabilitation.”

Records show that Liddell did spend three years, from 1960 to 1963, undergoing treatment at Atascadero State Hospital in San Luis Obispo County, during an era when some “sexual psychopaths,” later called “mentally disordered sex offenders,” were sentenced to prison hospitals. The state law providing for psychiatric placement was repealed in 1981.

Atascadero officials concluded that Liddell was “not amenable to treatment,” court records show. He was then transferred to Soledad State Prison, where he was held three more years.

Although the psychiatric records are confidential, Liddell maintains that he was kicked out of Atascadero because he took an unauthorized furlough one day into a nearby town and was caught with nasal inhalants in his pocket.

“In those days, nasal inhalers were the rage for kids for getting high,” he said.

Why indeed did I turn out this way?

Liddell traces his criminal behavior to the age of 5, when, he recalls, he stole a porcelain figurine from his aunt. He said his aunt later told him that she would gladly have given him the item.

The oldest of three children, Liddell described his mother as a strict, temperamental woman and his father as a mild-mannered, sensitive man with a drinking problem. His parents divorced when he was 12, and he stayed with his mother.

When he was 14, he was arrested on suspicion of burglary and placed in a boy’s home for orphans and delinquent children, court records show.

In a 1960 interview with a probation officer, Liddell said he has always been “different from others, kind of weird” and that he was a “Peeping Tom” by 13, growing “bigger and braver” as he became older, according to court records.

He became the “burglar on the block,” he said, as he began sneaking around his neighborhood at night to escape tensions at home. But he said he does not blame his parents for the way he turned out.

“They did their best,” he said. “I am responsible for my own behavior as an adult.”

Milestones in Prison

Nearly every milestone in his life has passed while he was in prison.

Liddell received his high school diploma from Salinas Adult School at Soledad Prison when he was 22.

In 1978, in a ceremony that was conducted in what he describes as a “closet storeroom” at Folsom Prison, Liddell married a woman he had known as a teen-ager. They divorced six years later, with all but five months of the marriage having passed with him in prison.

Liddell’s modus operandi is to ride a bicycle into familiar neighborhoods and to avoid patrol cars by traveling back alleys and monitoring police calls over a short-wave radio, using an earphone.

After the escape last year, the police were certain that Liddell would return to the haunts of his youth.

A month later, he was apprehended as he rode a bicycle one morning to a convenience store on Tampa Avenue in Reseda. The investigators who were searching for him had stopped there for a cup of coffee.

Police said Liddell’s pockets were stuffed with cash and jewelry from several homes that had been hit during the night. His radio scanner was tuned to the police frequency.

He did not resist arrest.

Although there was no evidence that he had contacted his mother, detectives later learned that Liddell had been renting a guest house two blocks from her Reseda home.

Liddell is aware that, if he is convicted of even a few of the current charges against him, his next prison term may see him through middle age.

“The thought of being buried off in prison for the longest period yet is very depressing,” Liddell said. “I’ll be so old.”

But he gives no guarantees that his pattern will change, saying only that criminal tendencies traditionally wane as an individual grows older.

“People kept pointing out that there were so many things I could have done,” Liddell said. “Why indeed did I turn out this way?”

LIDDELL’S CONFINEMENT HISTORY

Age 14

October, 1957 to November, 1957: ar rested for burglary; sent to boy’s home for delinquent children and orphans. Confinement Period 2 months

Age 14

April, 1958 to May, 1959: arrested for burglary; sent to Juvenile Hall and California Youth Authority. Confinement Period 1 year

Age 16

June, 1959 to November, 1959: arrested for burglary and parole violation; sent to California Youth Authority.Confinement Period 5 months

Age 16

January, 1960 to June, 1966: convicted of burglary, attempted rape; sent to L.A. County Jail, Atascadero State Hospital, state prison; declared “sexual psychopath.” Confinement Period 6 yrs. 6 months

Age 23

October, 1966 to November, 1975: convict ed of burglary, attempted rape; sent to L.A. County Jail, state prison. Confinement Period 9 yrs. 1 month (longest period out of jail-- 1 yr.)

Age 33

October, 1976 to February, 1982: convicted of robbery, burglary, attempted rape, oral copulation; sent to L.A. County Jail, state prison. Confinement Period 5 yrs. 4 months

Age 38

April, 1982 to July, 1983: convicted of burglary; sent to L.A. County Jail, state prison. Confinement Period 1 yr. 3 months

Age 40

October, 1983 to May, 1984: arrested for parole violation (petty theft); sent to L.A. County Jail, state prison. Confinement Period 7 months

Age 41

November, 1984 to present: arrested for burglary, assault with intent to commit rape; sent to L.A. County Jail, Pitchess Honor Rancho, where he escaped in March, 1985, captured in April; currently awaiting trial. Confinement Period 1 yr. 2 months

Total Confinement Period: 25 yrs. 6 months

Compiled using state prison records, court documents, interview with Liddell.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.